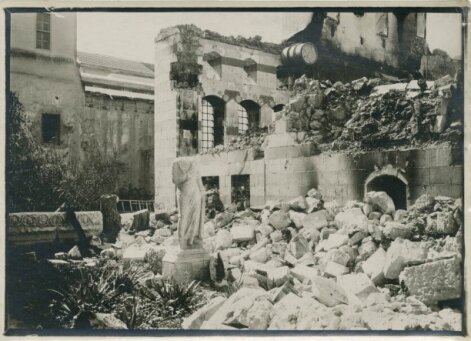

Smoke over bombed Damascus, 1926.

Photo: Luigi Stironi \ Massachusetts Historical Society

Syria met the end of the First World War with triumph and joy. Jubilant crowds greeted the Allies of the Entente – the British, Australians, New Zealanders, the French – as liberators who brought them long-awaited freedom, peace and prosperity. However, the tables have turned to confusion, anger and bitterness, when it became clear that yesterday’s allies and brothers-in-arms helped to demolish the old political regime only in order to create a new one on its ruins, but according to their own patterns and rules. There was no place for the locals, again.

The division of the Arab territories of the Ottoman Empire between the victorious countries in 1918-1919, and the Paris Peace Conference, which was extremely humiliating for the Arabs, demoralized many Syrians. A bold but doomed attempt to rebel against former friends and allies led to the tragedy of the Battle of Maysalun in July 1920 and to the collapse of the short-lived (first and only) Kingdom of Syria.

The former emir, the first and last king of Syria, Faisal, hid in neighboring Jordan. Until the end of his life, he lived under the forced protection of the British, whom he initially trusted, at the same time admiring his resourcefulness, however despising himself for resigning to this fate, At the end of the day, he agreed to sit on the throne of Iraq.

We recommend you read – “The day when Syria cries: the battle of Mayslun, and the will and aftermath”.

For Syria, 1919-1920 was a turning point in aspects. The Versailles-Washington system, which was established after the war, began to crack in many places, and, perhaps, the deepest and most visible of these wounds were in Levant and Syria. After the dramatic rise and rapid fall of the Syrian kingdom, this land has not seen peace.

The French, who hastily began to rule the territory under the mandate, immediately faced an extremely aggressive and toxic environment that pushed them out, as if it was a foreign body. The death of the founder of the Syrian army, Youssef al-Azma, near Mayslun had a strong psychological impact on the local population and set off a chain reaction that triggered a wave of anti-French riots and insurgencies throughout Syria, which Paris had to deal with throughout the next decade.

The story that not many know of, just like the battle of Mayslun or the Kingdom of Syria itself.

The Great Syrian Uprising of 1925 is one of the most significant events that determined the political development of future Syria and in some way influenced the course of its history right up to the present day. Just like the tragedy of 1917-1922 in Ukraine still lives in the public’s subconsciousness and determines some political discussions, with a barely noticeable shadow hanging over the Second Ukrainian Republic, so did the Syrian uprising of 1925- its rise, swing, fall and extinction left a deep imprint in the national memory of the country, which in 1946 will receive its longed-for independence, although it will not see peace and stability for a long time.

Levant’s “Ring of Fire” and the reasons for the uprising

When the French arrived in Syria and began to establish their own order in this territory, it was extremely difficult for them. The whole country was on fire. The promises and persuasions of Europeans, heavy battles with the Ottoman Turks, heroism and death of fellow tribesmen, arrests and executions of traitors, triumph and joy of victories were fresh in memory. The last thing the local Syrians wanted, were new invaders on their shoulders. Rebellions, riots, and unrest broke out everywhere. The French army barely had time to cope with them.

In 1919, the influential Alawite sheikh from Latakia, Saleh al-Ali, organized the first major anti-French protest, when Paris tried to intervene in its internal clan disagreement with other sheikhs. Al-Ali gathered 12 sheikhs of the Alawite tribes, and persuaded them to unite and march against the French headquarters in Latakia. The fighting lasted the whole of 1919, and only in the summer of 1921, after the defeat of the Kingdom of Syria, General Henri Gouraud, with the support of the British General Edmund Allenby from Palestine, and thanks to the neutrality of Mustafa Kemal in Turkey, was able to suppress the Alawite uprising. Saleh al-Ali went deep underground and disappeared from sight.

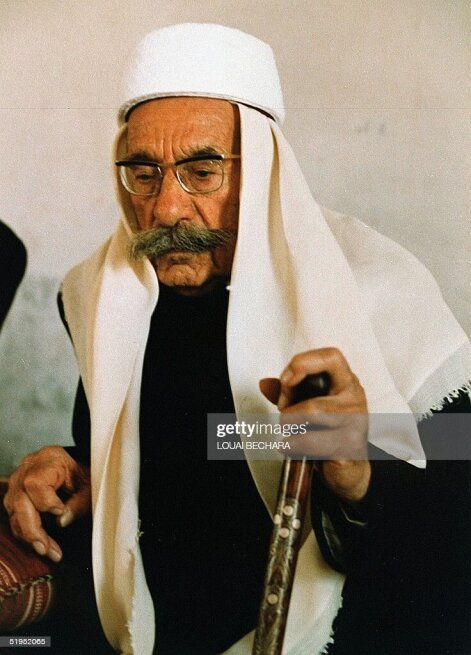

Sheikh Saleh al-Ali

The uprising of Sheikh Saleh al-Ali in 1919 was one of the strongest actions of the impoverished Alawite peasants from the province, not only against the French rule, but also against a system dominated by wealthy Sunni families on an urbanized coast.

In 1920, in Aleppo in northern Syria, an anti-French rebellion was raised by the local Kurdish nationalist Ibrahim Hanano. Inspired by the heroism of Yusef al-Azma near Mayslun in July of the same year, Hanano decided on making a daring uprising and practically crushed the entire city and its surroundings under him. Only by mid-1921, French troops were able to break the resistance of the Aleppinians and regain control of Aleppo. Hanano was arrested in 1922 and sentenced to death, but soon released as a result of his agreements with Paris and the reluctance of the French to escalate the situation even more, killing one of the brightest leaders of the nationalists.

Ibrahim Hanano

Ibrahim Hanano became one of the few Kurdish public and political figures who entered the pantheon of heroes of the Arab nationalist movement.

The turbulent years 1920-1922 restricted the French from a spectacular and graceful appearance in Syria. The new colonial administration faced some serious challenges, as well as enormous difficulties in communicating with local elites and officials.

A lack of understanding of local customs and traditions, a sense of their own superiority, a mocking imperial attitude towards the “aborigines”, a hesitance to present themselves as equals in negotiations with the Arabs, led to the fact that France, at the start of its rule on mandated lands, suffered defeat, primarily ideological and cultural.

One of the main reasons for the 1925 uprising was the complete out-of-sync between the French colonial authorities and the Syrian elites. In Paris, they were convinced that the Syrian Arabs are not able to rule their country, that they are barbarians, who know nothing about the government, therefore trusting them with serious duties and positions is delusional. This mistake will cost France dearly, and will “lay the seeds” for the future humiliating escape of the French from the Levant after the Second World War, which will be one of the most terrible and unpleasant moments in Charles de Gaulle’s career.

During the Ottoman Empire, the Syrian Arabs were incorporated into government institutions through the “millet” system. The late Ottoman Empire assumed the wide participation of local elites in the management of the region. The Millets allowed the Ottomans to divide the people of the empire along religious lines, as well as to give them a share of independence in some important matters to them, such as health care, legal proceedings, education and religious practices and norms. Of course, millets did not present complete freedom of action, and the primacy of Islam prevailed in the empire. The heads of the millets (spiritual leaders of the communities) were obliged to obey the Turkish sultan. Despite this, the local population and local elites had their own self-government and controlled some of the most important aspects of the life of the provincial centers and their communities.

The French (at least those who came to rule Syria) knew practically nothing about the intricacies of the Ottoman institutions of government. They had no idea that the disintegration of imperial power in Istanbul did NOT mean that power at the local level would simply disappear and everyone would have to be urgently saved from their own ignorance, lawlessness and anarchy. Therefore, official Paris hastened to take over all management functions, appointing its representatives at almost every level of the state bureaucracy and assigned administrators to oversee the Syrians, “teaching” them how to manage their land.

This irritated local officials, who did not want to be taught about life in their own cities and regions, telling them how old, underdeveloped and insufficiently independent they were (also taking into account the wounded sense of their own pride, which is traditional for Arabs).

Moreover, the French emissaries often ruled the territories themselves instead of educating the locals, therefore, over time they took over local power. As a result, a whole group of the urban bureaucratic class emerged, who opposed the “civilizational” mission of France and did not want to be treated like idiots. In addition, the French violated their usual social order when they opened the doors of the civil service for everyone, thereby eroding the authority and influence of those Arab (especially Sunni) families, who for many decades and centuries served as hereditary administrators in these provinces and big cities.

The French authorities also failed to find a common language with the tribes of Syria that lived around large urban centers. The rapid, ruthless industrialization and urbanization, which the French authorities rushed to pursue, without taking into account the mood of the rural population (Bedouins in the east, Ismailis in the center, Alawites on the coast, Druze in the south) and their interests, led to a change in the usual social environment of the Syrian tribes, as well as embittered them, convincing them that France was a threat, and that the colonial authorities allegedly wanted to take their lands. The influx of Armenian refugees and Kurds from neighboring Turkey from the north only worsened the situation: the tribes did not want to share territory and power with foreigners who had arrived here. And since Paris supported Mustafa Kemal, the Syrians blamed all the troubles from the wave of refugees on the French. The last straw was the new taxes of the French on livestock, which was the main source of income for the tribes, as well as the ban on the carrying of weapons by Bedouins in settlements.

Syrian Arab nationalists, who in the post-war period became a new opposition to the old post-Ottoman urban elites, initially had a negative attitude towards the French authorities, and the French, in turn, after starting negotiations with them, did not complete them, although the French leadership allowed (for the first time) the creation of political parties in Syria. The first was the nationalist People’s Party, which later joined the anti-French uprising.

Finally, it is worth remembering another social group, which, in fact, started this whole mess. The Druze have lived in the southern regions of Syria for a long time, at least since the second half of the 17th century, when they began to migrate from Lebanon to the mountainous regions of the current Syrian province of Al-Sueida. The local region of Jabal ad-Druz (translated from Arabic as “Druz Mountains”) – a volcanic area covered with a basalt blanket, dotted with craters and surrounded by lava fields – stretches across southern Syria and parts of northern Jordan. A huge fertile land begins to the northwest and west of these rugged mountainous regions.

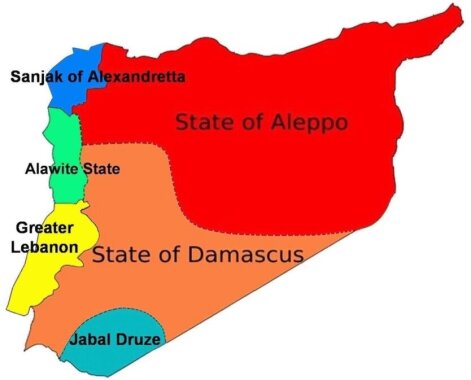

“Divide and rule” became the foundation of the French colonial policy in Syria. Therefore, immediately after the liquidation of the Syrian Kingdom in 1920, France divided the territory of Syria into 6 self-governing quasi-states: Alexandretta Sanjak, Alawite State, Greater Lebanon, Jabal ad-Druz, Damascus State and Aleppo State.

The complex specifics of the Druze culture, the uniqueness of their rituals, the differences in beliefs from traditional Islam and Christianity made these people – hardened by mountain life, somewhat isolated from the rest of society, and their living environment isolated them from the rest of Syria.

The Druzes most often stood away, trying not to interfere in the affairs of other communities, but to defend their small home in the mountains by not letting in any strangers, primarily from the neighboring province of Daraa. Unlike other regions of Syria, such as coastal Latakia, there were no serious inter-confessional conflicts in the south of the country, since the overwhelming majority of the population were Druze, like the entire local elite. If disagreements did arise, it was exclusively within the Druze community itself. Representatives of other religious communities never ruled in their region – there was no dominance of some over others with an attendant inter-confessional tension.

Because of this, the southern region of Al-Sueid has always had a strong local identity as well as a strong social community. They often spoke out as a whole against the attempts of the center to impose its power, whether it was Istanbul, Paris or Damascus.

When the French came to Syria, the Druze were not very happy about it. When France occupied Syria, they divided the country into six quasi-state entities. On the one hand, this made it possible to govern the country according to the principle of “divide and rule”, putting different ethno-religious groups against each other when it was necessary. On the other hand, the division of Syria allowed the French to govern separate regions in their own way, and to appoint their “overseers” there.

The southern regions inhabited by the Druze were divided into a separate administrative entity, which was nominally ruled by the Druze, but in practice the governors were appointed by France. Aggressive attempts by the Europeans to impose their power were met with resistance by the Druze sheikhs, and soon, an attempt by the French to intervene in the election of the Druze supreme leader completely unbalanced the still unformed relations between the two sides. This is where the story of the Great Syrian Uprising begins.

Honor and Courage: Obligations for Rebellion

Tensions between the French colonial administration and the local population of the Jabal al-Druz region reached their peak by the summer of 1925. Local Druze leaders have repeatedly complained about French officials and managers, demanding them not to interfere in their lives, raise taxes, and arrest their family members for disloyalty or failure to comply with laws. To prevent bloodshed, a group of sheikhs from the main Druze clans demanded to have a meeting with the French High Commissioner in Syria, Morris Sarray. The French did not want to meet, considering the locals to be barbaric, as well as they didn’t want to show weakness, in order to set an example for other regions.

Finally, on July 12, 1925, under the pretext of “discussing the complaints received by the local garrison,” the High Commissioner of France invited five elders of respected Druze clans from the south to his home in Damascus. Among those invited was the young Sultan Al-Atrash – the future leader of the revolution, with whom everything will begin. However, him and another sheikh refused to go to the meeting, since they had already decided that it was useless to talk to the French. The other three went to Damascus, hoping to settle their problems and have a constructive conversation with General Sarah.

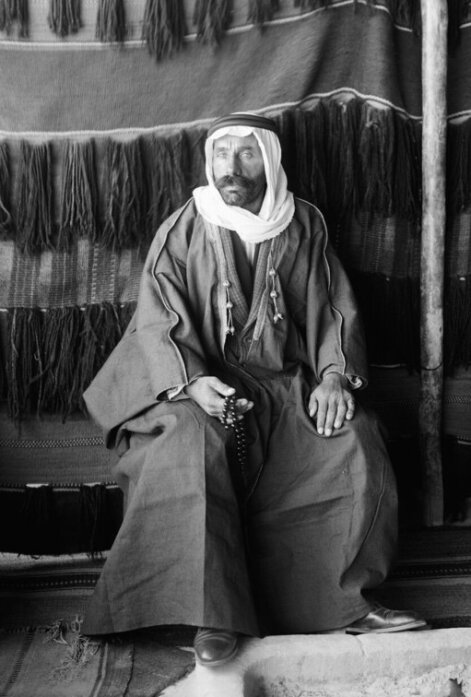

Druze sheikh Sultan Al-Atrash

The young Druze sheikh Sultan Al-Atrash came from a family of rioters who fought all the time, either for their survival, for their leadership, or against some foreign enemy. Sultan Al-Atrash’s father was executed by the Ottoman Turks in 1911 for organizing an uprising. The atmosphere of constant struggle tempered Al-Atrash and in many ways shaped his character, which played an important role in the 1925 uprising.

Upon arrival in the Syrian capital, they were immediately arrested and imprisoned. By the order of the High Commissioner, they were taken from Damascus to a deserted prison far east off Palmyra. The arrest was the last straw for the Druze, after which they became angry. The remaining two sheikhs – Sultan Al-Atrash and Sheikh Mitaab, who did not go to Damascus, began to prepare an uprising.

By that time, relations between France and Al-Atrash were already completely ruined. The match that set the fuse on fire, followed by an explosion in 1925, was the so-called “Adgam Khanjar incident.”

On June 23, 1921, a group of Lebanese and Syrian nationalists attempted to assassinate the commander-in-chief of the French troops in Syria, General Henri Gouraud – the same one who defeated the Arabs in the battle of Maysaloun a year earlier and liquidated the Syrian Kingdom. The assassination attempt failed, although the general nearly died. His driver and the local governor sitting next to him were injured. Gouraud’s assistant, Commandant

Branne, was killed, and the general himself was wounded in the arm.

After the failure, the participants in the assassination attempt fled to Jordan. One of them, the Lebanese Shiite Adgam Khanjar, moved to the south of Syria, where he received refuge from the Druze of Sultan al-Atrash in his family estate in the village of Al-Qaraya. A couple of days later, Khanjar was arrested by two French soldiers who met him in the street.

Al-Atrash condemned the arrest and asked to return the prisoner, since he was a guest of his house, and this was incredibly important for the Druze. The arrest of Khanjar was perceived as a personal insult to Al-Atrash and as a big violation of Druze traditions of hospitality, which undermined their authority. Sultan al-Atrash offered to exchange Khanjar for several French soldiers who had been held captive by the Druze as a result of earlier clashes. The French authorities agreed to the exchange.

Then, the irreversible happened. When their soldiers were handed over to the French, they opened fire on the Druze negotiators, refused to return Khanjar and left. For Sheikh al-Atrash, this was a mortal insult: the Europeans not only “stole” his guest, violated the boundaries of his family estate, humiliated him in the eyes of the community, but also “threw him off”, by breaking a promise. The Sheikh was so upset and offended, that according to some of his associates, he even burned down his own house, saying that "a house, the gates of which cannot protect anyone, should be set on fire." Adgam Khanjar was taken to Damascus, judged and executed in the same 1921, consequently Sultan Al-Atrash harbored a grudge against the French and refused to deal with them, therefore he did not go to Damascus on that unfortunate day on July 12, 1925, thus avoiding arrest.On July 13, the day after the arrest of the Druze sheikhs, Al-Atrash and his associate, Sheikh Mitaab, began mobilizing their supporters and Bedouin fighters to attack the French garrison, which was based in the town of Salhad in the province of Al-Sueida.

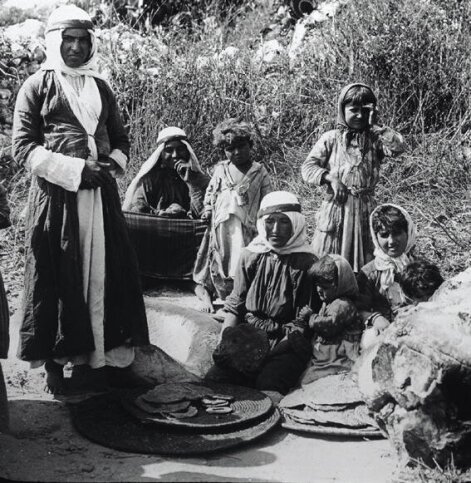

Druze women, 1920’s

The first shots of the future uprising were fired on July 19, 1925. Al-Atrash’s forces shot down a French reconnaissance aircraft over the village of Urman. Both injured pilots were captured and placed under house arrest at the Al-Atrash family estate. The remains of the plane were burned. A day later, on July 20, the soldiers of Sheikh Al-Atrash, numbering about 200 people, captured the town of Salhad without a fight, forcing the French garrison to surrender. The Druze offered the French authorities to return the captives, exchanging them for the sheikhs arrested on July 13, but Damascus refused this offer.

Instead, after hearing of the news from the south, the colonial authorities decided to quickly put an end to the rioters, and sent reinforcements to the province - detachments of Syrian and Algerian Sippahs and fighters of the Syrian French Legion (mainly Tunisians), led by Captain Gabriel Norman. There were 160-180 of them. Sultan Al-Atrash sent his representatives to the commander of the punitive units in order to persuade them to make an exchange and end everything peacefully: the sheikh was not sure of the success of his campaign, and he did not have a goal to fight with all of France, realizing that his forces would not be enough. The French refused to negotiate, and Captain Norman decided to carry out the instructions of the capital - to pacify the rebellion, disperse the Druze and arrest the chief troublemaker who dared to rise up against France.Battle of Mazraa, Druze triumph and the point of no return

The beginning of the Great Syrian Uprising is considered to be July 22, 1925, when cavalry detachments loyal to Sultan Al-Atrash attacked the French military column of Captain G. Norman near the village of Al-Kiafr in the mountainous regions of Al-Sueida province on the way to Salhad. The French were taken by surprise. Less than half of the soldiers survived, the rest were killed in just half an hour. This was the first military victory for young al-Atrash, after which people from the surrounding area were drawn to him.

Inspired by the victory, pleased with the arrival of reinforcements from among the local, taking advantage of the confusion and demoralization in the ranks of the enemy, the forces of Al-Atrash laid a siege to the provincial capital, the city of As-Sueida, where the headquarters of the French administration were located. It was at that moment that the parties realized that everything was serious: the French began to perceive the Druze as a real threat, and the Druze believed that they could overturn the situation in Syria.

The victory at Al- Kyafr and the struggle of Sueida convinced the hesitant Druze sheikhs to support Sultan Al- Atrash. In just a couple of days, his strength grew from a small detachment of a couple of hundred people to a 10,000-strong army capable of challenging the French rule in at least southern Syria. On July 29, Al-Atrash’s Druze troops began to undermine communications and transport hubs linking South Syria with Damascus, in order to prevent the French from sending reinforcements and slow down their progress. On that day, a section of the railway between Damascus and the city of Daraa was blown up, as well as the road between Al-Sueida and the town of Israa in the west.

The French began to collect a new punitive expedition to the fiefdom of Al-Atrash, and soon launched terror against the local population. About 1,000 French soldiers, as well as more than 2,000 Algerian and Syrian Sippahs, united in the province of Daraa and left towards Al-Sueida from the west, passing through the arid plains of Bosra al-Harir. They stopped at the village of Al-Mazraa, which was located on a flat area just on the border with the mountainous region of Jabal ad-Druz. The Druze watched the movement of the French, as the hills and mountain peaks offered good views of the western plains, giving Al-Atrash an advantage over the battle.

It took place on August 2-3, 1925, and will be the event that will finally undermine the powder keg of the uprising. Punitive detachments of the French under the command of Major Jean Oyak and General Roger Michaud were ambushed by Sultan al-Atrah and underestimated the enemy. In the bloody battle of Al-Mazraa, their 3.5 thousandth army was defeated. More than 1,000 French soldiers were killed (mainly African fighters from Madagascar and Senegal). The rest were captured or wounded, including Major J. Oyaka. The commander of the French Madagascar detachments fled the battlefield and later shot himself.

Al-Atrahs forces won a serious military and political victory, as well as impressive trophies – more than 2,000 guns, ammunition and several artillery installations and machine guns. On August 11, negotiations finally began between Al-Atrah and the French administration. Paris became more compliant, and agreed to release the Druze sheikhs arrested on July 12, as well as to release the rest of the prisoners. The Druze gave their prisoners to the French. The commander of the colonial forces in this battle, General Roger Michaud, this defeat cost his career: he was recalled in France.

The result of the Battle of Al-Mazraa was impressive, especially for the French public. Their country has lost control of almost all of South Syria. The French garrison in Hausweid, exhausted by the siege and deprived of resources and food, surrendered on September 24, and evacuated from the province.

Sultan Al-Atrash became the undisputed leader of the Druze clans. He consolidated his power in the south and received the approval of all other sheikhs. It can be said that it was in the heat of the Battle of Al-Mazra’a that the 34-year-old Sheikh had long staked the status of a moral and political authority in Jabal al-Druz, as well as cemented his influence and heritage for many decades to come until independence.

His victory inspired the nationalist underground throughout Syria, inspired them that the fight against France did not end in 1920, and could even be successful. Al-Atrash was noticed not only by his brothers and neighbors, but also by other prominent Arab nationalist figures.

A gathering of the Druze sheikhs, 1926

What began as a purely local disassembly in the Druze world splashed out of the closed mountain range of the Suida, and covered the entire territory of Syria, contributing to the ascent of the “stars” of the nationalist movement, who in the future will become architects of the independence of modern Syria, Lebanon and Iraq.

National fire and French counteroffensive

Despite negotiations and the exchange of prisoners, there was no peace after the Battle of Al-Mazraa. France couldn’t tolerate such humiliation. In Paris, of course, they were disappointed with the military failure in the south, but they were determined to continue the struggle, believing that a large-scale and long war of the Druze would not be pulled. In the end, they were right.

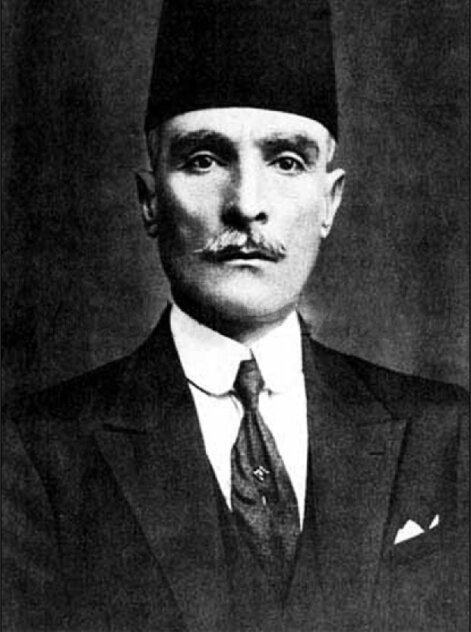

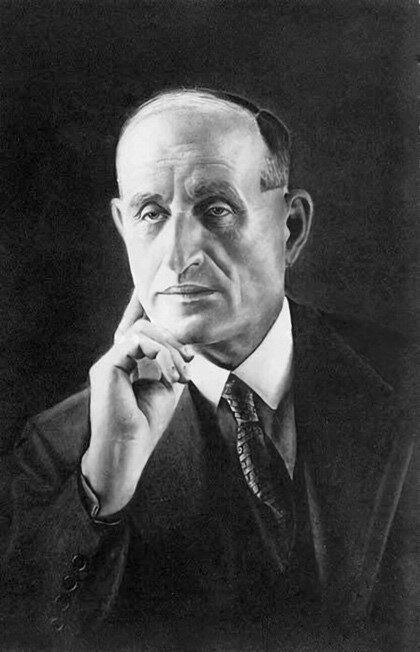

The High Commissioner of France to Syria, General Morris Paul Sarray, was a tough, uncompromising, suffy and very impatient man. As a Republican socialist in a predominantly conservative country with still strong monarchical feelings, he was always an outcast. He was disliked by colleagues, some friends did not understand him, and he made his military career largely thanks to his political allies socialists in government and parliament.

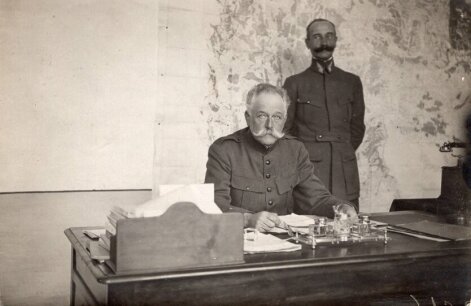

General Morris Sarray in the years of the First World War, 1916.

He was a soldier man for whom endurance, firmness of character, principledness and commitment to established views were fundamental. Political and ideological outsiderness hardened his worldview and tempered his character, which often resulted in quarrels with colleagues-generals, disputes with the management, unauthorized and bold decisions that almost cost him his career. Each time he was saved by some mystical luck, a combination of circumstances and acquaintances at the political top.

General Sarray got his job in Syria not because he wanted it, but because he was actually exiled here out of sight. This was probably also one of the reasons for the bad mood he often stayed in when he was in Damascus. The challenge he was given to by the local elites he despised was perceived by the elderly general as a mockery. People always argued whether it’s going to be the end of his already difficult and unrealized career? Will these barbarians defeat him? Him, the hero of Marne and Ardennes, the savior of Verdun and Thessaloniki?

General Sarray spent most of his military career after graduating from the prestigious St. Seres Military Academy in military administrative. He was not allowed to jump above both because of his complex nature and because of his open socialist views. It was only after the rise to power of Prime Minister Joseph-Marie Cayo that Sarray had a chance to advance his career ladder.

In 1911, him, already a 55-year-old staffman, was appointed to the first serious leadership position – commander of the infantry division. And the Great War of 1914-1918 gave him a chance to prove himself, demonstrate his skills and talents. Nonetheless, he didn’t do it very well.

After relative success during the Ardennes retreat in August 1914, General Sarray’s 3rd Army lost a major battle at Marne in September. At the same time, he made a number of risky decisions contrary to the opinion of the command, which worsened the French position near Verdun, which Sarray was accused of.

Further quarrels and disputes between him and his leadership led to the fact that the French were unable to develop a counteroffensive and make progress. Throughout the winter of 1914-1915, Sarray spent trying to knock German troops out of the Obrevilla Heights, which they captured during the offensive on Marne. But his attempts were in vain. His 3rd Army lost 10,000 people in these battles in November alone.

When Maurice Sarray was transferred to the Thessaloniki Front in Greece in 1915, he was also facing a fiasco there, first during the offensive against the Serbian city of Cherna, and then when his forces were forced to retreat to Thessaloniki. In general, Sarray’s entire Balkan campaign was a complete failure, and if it had not been for the patronage of his Socialist comrades-in-arms in the government, the general would have been fired long ago. Actually, that’s what happened in 1917. When the socialist government collapsed and Prime Minister Joseph-Marie Cayo and Jean Malvi were accused of treason, Morris Sarray’s front story immediately ended. He was fired and sent to his estate, where he stayed until the end of the war. And in 1924, when the Socialists came to power again, an old general, who still dreamed of doing something outstanding, was appointed to Syria. And now we’re going back to our 1925 uprising.

After the Battle of Al-Mazraa, despite the signing of a truce with the Druze, France could not tolerate such humiliation. Thousands of colonial troops were transferred from Morocco, Senegal and Algeria to Syria at the request of General Sarray. This allowed the French to seize the initiative and resume hostilities against the rebels, increasing pressure on al-Atrahs forces in the south. At first, they succeeded: the Druze managed to be pushed back into the province and forced to defend themselves again. In mid-August, the French army burned down the family estate of al-Atras. Until October, there were fighting between them, but Paris could not break the resistance of the rebels.

On August 23, 1925, in the middle of fighting, Sultan Al-Atrash publicly declared war on France, in fact, for the first time becoming the voice not only of his own people or clan, but also a reflection of national aspirations. Perhaps then, Al-Atrash himself believed that he could lead the masses and become a national hero. Fame irritated his ambitions, pushing him to such a brave act that not only radicalized the conflict, but also became a point of non-return in the relations between al-Atrash and the French administration.

Sheikh Sultan Al-Atrash with his troops, October 1925. Photo: Library of Congress.

The Druze Sheikh called all ethnic and religious groups in Syria to resist the occupying forces and called a significant number of people led by prominent nationalist underground figures, famous politicians, craftsmen, urban intellectuals, influential landowners and bankers, former Ottoman-Arab officials such as Hassan al-Harrat, Nassib al-Bakri, Abdel Rahman Shahbandar, Mohammed Al-Ashmar, Said al-As, Mohammed Al-Ayash and Fawukji. Inspired by the example of the Druze, they rebelled in their fiefdoms, shaking the situation in several key regions of Syria.

In September 1925, a revolt broke out in Al-Gut near Damascus, which was led by local influential nationalists Hassan al-Harrat and Nassib al-Bakri. On October 4, 1925, nationalists led by Fawzi al-Kavukji rebelled in the city of Hama. In the same month, they captured the town of Maaret al-Numan in southern Idlib province, forcing the French to take some troops from southern Al-Swaida and move them northwest, giving Al-Atrash more freedom of maneuver and opening the way to the Hejaz Railway and Damascus from the south.

In the same month, the Syrian nationalist People’s Party under the leadership of Abdel Rahman Shahbandar joined Al-Atrash forces, able to mobilize supporters in the vicinity of Damascus and in the capital itself.

A one-momental riot from all directions disoriented the French at once, and contributed to the rapid success of the nationalists, who even captured Damascus on October 18, 1925, albeit for a short time: just a month later, the French repulsed him back. With the beginning of winter, the leadership of the French administration made a tactical mistake in deciding to pause and accumulate strength, which gave al-Atrash more time to gather troops, and regional rebellions turned into a national uprising when Homs, Daraa and Deir al-Zor broke out.

However, the Arabs could not withstand a long war. It was clear from the beginning. The nationalists tried several times to negotiate with General Sarray, but he refused, knowing that he had superiority in both number and quality. That’s why even a winter pause didn’t help the participants of the uprising. They could not achieve their rapid and even unexpected success for themselves, nor could they gain a foothold in the occupied territories. After all, they failed to raise all the provinces completely, only certain areas and cities rebelled. The rebels lacked weapons, ammunition, data on French troops, not to mention armored vehicles, aviation and heavy artillery. As a result, they were just crushed by numbers, skill and technique. By the end of spring 1926, the rebels ran out of steam, and the French gradually seized the initiative and began to return the lost territories.

Sultan Al-Altrash in Arabia, just after getting defeated by the French, 1926

The decisive battle was the Battle of al-Mushairif in Al-Suaid Province, in which the French defeated the combined forces of Sultan Al-Atrash, forcing him to flee to Saudi Arabia, then to Jordan, where he remained in exile for 10 years before he was allowed to return.

Until the autumn of 1926, all other riots were suppressed. Hassan al-Harrat was killed in the battles in Al-Ghut, his son Firas was captured and hanged in the square in Damascus to edifying others. Nassib al-Bakri and Abdel Rahman Shahbandar fled to Iraq. The uprising in Deir al-Zor, where the influential tribal sheikh Mohammed al-Ayash raised the locals, was brutally suppressed by September. 12 closest associates of al-Ayash and his son were executed, and the most powerful Arab sheikh and his family were sent to the coastal city of Jabla in Latakia, away from their home.

In Idlib, everything ended after the French victory in two battles near the villages of Kyafr-Taharem and Tal-Ammar in March-April 1926. The uprisings in Hama and Homs could have dragged on for years if the rebels had managed to cut off the French communications, but they did not do so, and concentrated all their forces in the cities in anticipation of punitive detachments that easily defeated them by mid-1926.

In addition to the lack of resources and the apparent preponderance of French forces, the rebels had another problem – the local population was not ready for another protracted war, and many remained demoralized after the events of 1919-1920. Despairing and pessimistic sentiments after the liquidation of the Syrian kingdom created difficulties in mobilizing supporters. Some parts of the population simply did not believe that from the small local revolt of the Druze Sheikh somewhere in the south, with which the rest of Syria had not come into contact, it would be possible to raise a real wave that would sweep away foreign occupiers. In addition, many feared repression and persecution by France, especially after the indicative executions of some leaders of the uprising.

Finally, the “divide and conquer” policy pursued by Paris sowed grains of mistrust between communities, and contributed to the growth of locality and isolation between different regions. The Alawites, who have long been under the oppression of wealthy Sunni urban families on the coast, received the long-awaited self-government within the framework of the “Alawite State” created by the French. Christians, disadvantaged by the vast majority of Sunni Muslims, were also protected and began to promote them to high positions in Mandated Syria. The urban Ottoman-Arab elites of the north became the head of a separate state entity with the center in Aleppo, and thus the rivalry between Damascus and Aleppo was formalized and separated thanks to Paris.

In short, as a result of manipulation of the administrative and territorial system and agreements with local elites, there was a layer of pro-French Syrians who gained power or influence after the arrival of Paris.

This does not mean that the ideas of Arab nationalism were no longer popular. More likely, people were tired of wars, did not recover from the shock of 1920, and were not sure of the success of the uprising. In addition, the French themselves did not sit idly by, and understood perfectly well: to put out the uprising, it is necessary to persuade at least part of society to your side. Therefore, in February 1926, the administration held early elections in Syria and declared amnesty to the rebels. People willingly supported the idea of elections, and went to vote, believing that “a bad world than a good war is better”.

The collapse of the Peace of Versailles and the legacy of 1925

The Great Syrian Uprising left a deep impact on the entire generation of Syrians. Like the events of 1919-1920, anti-French speeches brought even greater discord in the relations between the French administration and the local population, sowing hatred and contempt for each other. Many Syrians who did not participate in the uprising, although they resigned themselves to French rule, did not become loyal to Paris, and soon encouraged the fall of the colonial administration in the next 20 years.

More than 6,000 rebels were killed in battles, and under 100,000 people were displaced. Many moved to Damascus and Hama, who could not cope with such an influx of refugees. Many people were impoverished and had to rebuild their lives for decades to come. In large agglomerations, toxic social groups that hated the French were formed, and their children became the core of another anti-French protest in the 1940s, which led to Syria’s independence in 1946.

We recommend reading: “Syria and Lebanon in World War II“.

The leadership of the French administration was forced to change their approaches to colonial governance in the Levant. Direct governance was found to be too expensive and ineffective. More and more locals began to appoint to different positions, and in disputes they preferred diplomacy and negotiations to force, fearing another explosions.

This has significantly increased Syrians’ access to the administrative apparatus and public administration system. And in March 1928, France declared an amnesty for the participants of the uprising. However, this still did not help Paris to retain control of these territories. Many French continued to treat the locals as second-class people. The Syrians did not cease to consider the French occupiers and foreigners, and the antagonism between them increased, resulting in the tragedy of 1946 and the shameful evacuation of France from the Levant, and at the same time a triumph for Britain, which used the deterioration of the French position in Syria and Lebanon, and supported anti-French forces among nationalists.

To recapture Damascus from the rebels in November 1925, General Morris Sarray ordered massive artillery bombing of the city, which resulted in the death of 1,500 civilians and terrible destruction. Damascus’ shooting was so monstrous that it even caused discontent in Paris. The trauma caused by this event sat in the minds of a whole generation of citizens, angry them and created a huge social base for nationalists, which soon brought them to power and dared French rule in these territories.

The destruction of Damascus after the shootings of 1925 was the worst in decades. They left a massive wound in the minds of Syrians, which happened again in 1946: when the French also made shootings in Damascus, while trying to hold onto power. Photo: Luigi Stironi.

The shootings of Damascus destroyed General Sarray’s career. His enemies now had a justified reason to finally get rid of him. The government dismissed him from the post of High Commissioner of Syria and withdrew him to France, where he retired. Broken by another defeat and his seemingly universal injustice to him, 2 years later the general died in his house near Paris.

As I have already written, the 1925 uprising formed a galaxy of bright, charismatic leaders who later played a decisive role in the struggle for independence and the building of the Syrian state within its modern borders after 1946.

The leader of the anti-French uprising in Aleppo, Ibrahim Hanano, became a national hero. The French did not dare to execute him or send him into exile, and in the following years he did a lot to preserve the anti-French sentiments that bubbling at the grassroots level in his hometown, and also persuaded his Kurdish community in Aleppo to support the nationalists. In 1933, he was even killed, it was said that it was because of his activities against Paris. In 1935, Hanano died of tuberculosis. One of the neighborhoods in Aleppo, where the Kurdish minority still lives, is named after him.

The leader of the Druze uprising, Sheikh Sultan Al-Atrash, returned to Syria after an amnesty in 1937. He became a symbol of nationalism and patriotism, continued to be the leader of the Druze, maintaining a dominant position among the clans of the south, defining life in the province of Al-Suida. Thanks to him, the Druze supported the nationalists, and after independence in 1946, al-Atrash actively participated in the political life of the country, although he did not want to go beyond his region or apply for national positions.

In 1948, he participated in attempts to create a unified Arab army in the war against Israel. In 1954, he was forced to leave Syria again due to a conflict with then pro-Western President Adib al-Shishakli, who seized power in the 1949 coup, but a few months later returned when the regime fell.

In 1958, Sultan Al-Atrash supported the unification of Syria and Egypt, and received the highest state award from the President of Egypt. After 1961, Sheikh al-Atrash began to develop his community and moved away from active public life, remaining a living legend for Syrian activists and politicians. Even Hafez Assad, when he became president, personally came to the house of Sultan al-Atrash, whom he deeply respected and revered. Thanks to him, the province of Al-Swaida and the southern Druze clans reached an understanding with the Syrian central authorities, and they have always been able to find compromises when disagreements arose. Sultan al-Atrash died in 1982 at the age of 94, becoming the oldest leader of the 1925 uprising.

Elderly Sultan Al-Atrash in Syria, 1976 Getty Images

Abdel-Rahman Shahbandar, one of the founders and leaders of the first Syrian nationalist People’s Party, vice-president of the interim government, which al-Atrash proclaimed in August 1925 when he declared war on France, continued to develop the nationalist movement after 1925. He returned to Syria after the amnesty of 1937, and led the political struggle against pro-French forces in the government, making a huge contribution to the nationalists’ retention of dominant positions in the political life of the mandated Syria. However, Shahbandar did not have time to see the result of his activities.

On July 6, 1940, he was killed at his clinic in Damascus by a group of Islamic fundamentalists. His case was never fully solved. The French authorities hastened to accuse the leaders of another nationalist party, the National Bloc, for his murder, forcing them to flee to Iraq. In February 1941, the murderers were executed, and this was put to an end in the case, although there were persistent rumors in the capital about the involvement of the French in the murder of the politician.

Abdel-Rahman Shahbandar was one of the pioneers in the formation of the Arab nationalist movement in Syria, since the appearance of the Young Turks in the Ottoman Empire. He was one of the most popular nationalist leaders in Syria, but did not have time to realize his potential and build a full-fledged political career.

Mohammed Al-Ayash, the leader of an influential clan from the “capital of eastern Syria”, the city of Deir al-Zor, who rebelled there in 1925, never returned home after battling there to Arwad Island near Tartus. The French considered it too dangerous, given its authority among the East Syrian tribes. In 1926, French intelligence agencies poisoned him and did not even allow him to be buried in Deir al-Zor so that his grave would not become a place of pilgrimage for local nationalists. Inspired by the example of Al-Ayash, his associate Ramadan al-Shallash revolted in the east again in 1941, and also unsuccessful.Fawzi al-Kavukji, Nassib al-Bakri, Mohammed al-Ashmar and Said al-As, who led anti-French demonstrations in central and northern regions of Syria, fled abroad, and subsequently became important advisers to the monarchs of Jordan, Iraq and Saudi Arabia, and helped them train the local Arab army in the hope that they would someday liberate Syria from foreign occupiers. Their anti-Western sentiments have further intensified since 1925, and they were angry, despising those Arab leaders who cooperated with France or even Britain.

Fawzi al-Kavukji

Fawzi al-Kavukji became of the most well known Turkmen Syrian nationalists, who took part in many wars during his life. Here’s him in 1936.

Nassib al-Bakri in the late 1930s became one of the founders of another powerful nationalist party- “National Bloc”, which launched a political struggle against France in Damascus, and remained in power until the late 1950s. Fawzi al-Kavukji managed to participate in the Palestinian uprising in 1936, fight in the Wehrmacht in 1939-1942, then fight against everyone in a row, be captured by the Soviets in 1945, and after liberation return to Syria and lead Palestinian armed groups in the war with Israel in 1948. Until his death in 1977, he lived in Beirut and Damascus, remaining a prominent nationalist figure and activist. Said al-As also went to war with Jews and British in Palestine, where he died in battles on the streets of Jerusalem in 1936. And Mohammed al-Ashmar followed politics in the footsteps of Abdel Rahman Shahbandar, and then hit religion in the 1940s only to become a fan of the Communists and the USSR in the 1950s and 1960s.

The Great Syrian Uprising of 1925 was one of the first gloomy omens of the further collapse of the Versailles system. The division of the Middle East between the Allies led to the emergence of artificial borders and the rapid growth of nationalism, and with it the aggravation of internal ethnic, religious, tribal and class contradictions.

France’s policy in the sub-mandant territories in Syria has exacerbated socio-economic contradictions between the province and the cities, the rich class of Sunni Muslims and the poor class of Shiite, Alawite, Christians and others. The rise of certain religious minorities in power at the expense of the interests of the Sunni majority has exacerbated the conflict between them. Subsequently, it will determine the position of minorities who will fill the ranks of the BAAS party, which aims to eradicate imbalances and injustices.

The Versailles system in the Middle East began to collapse almost immediately in the 1920s-1930s, although its breakthrough will last for as long as 100 years. The echo of the events of 1917-1925 in Syria is felt by the region and the country itself to this day.

For France, 1925 was a rehearsal of 1946 and the beginning of the end of their reign not only in Syria, but also in the Levant and the Middle East. For Syria itself, the 1925 uprising, as a sad page in history, was one of the main impetuses for the development of self-consciousness of individual regions, the growth of their own ambitions, and the foundation on which Syrian nationalism, especially Arab, grew. It was reflected in the person of the middle officer, the Baathists, who came to power in the 1960s and for the first time brought peace, stability and a kind of sense of community and national solidarity, although it did not yet start in all the regions.